What now for UK investors?

Fears abound of a UK recession and knock-on effect in Europe and beyond.

The investment markets have been struggling with the uncertainty surrounding the EU Referendum since the decision to hold the vote was agreed in February.

Now the UK has voted to leave the European Union after four decades of membership, the one thing most people can agree on is that there will be more volatility and more uncertainty.

David Cameron has provided some breathing space by passing the responsibility of triggering Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty to his successor, and perhaps as a result sterling has not fallen quite as far as some had predicted, while the UK stockmarket managed to find a footing in the days following the vote.

After the initial reaction, the critical issues for markets will now be the path that the UK chooses for exit

From here on in investors are entering the unknown: some highlight the potential opportunities, while others point to the likelihood of a recession in the UK and the knock-on effects across Europe, although perhaps not globally.

Noland Carter, chief investment officer at Heartwood Investment Management, notes the likely implications of the vote include “economic growth [that] will be vulnerable in the near term for both the UK and the eurozone. As evidenced by Bank of England (BoE) governor Mark Carney’s speech, the UK government and BoE will be proactive to support growth. A meaningfully weaker sterling may help to counter some of these negative forces longer term. It should be remembered that eurozone growth has been stable, but it is low at 1.7 per cent year on year and there is very little room for error.”

Meanwhile, a Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Research report in the wake of the result, ‘The Thundering Word: Brexit and the War on Inequality’, highlights that as an exogenous shock, Brexit “will lead to lower growth, lower rates and a stronger dollar. But it will also lead to a short-term tactical buying opportunity for risk assets, led by credit markets, once redemption fear passes and policymakers respond.”

Sterling has been hit the hardest following the vote, and the bad news has continued with the UK losing its prized AAA credit rating from S&P on June 27. The ratings agency downgraded the UK to AA on the basis that the Leave result “could lead to a deterioration of the UK’s economic performance, including its large financial services sector, which is a major contributor to employment and public receipts”.

Simon Down, senior portfolio manager at Nikko Asset Management, adds: “After the initial reaction, the critical issues for markets will now be the path that the UK chooses for exit and how the vote will affect the political backdrop in other European countries.”

Nyree Stewart is features editor at Investment Adviser

Expert view

Giordano Lombardo, chief executive and group chief investment officer at Pioneer Investments, says:

“The asset management industry will emerge from this decision without permanent major harm, though in the short and intermediate term there will inevitably be volatility and uncertainty. So-called ‘risk assets’could see downside volatility for some time. Uncertainty on the future of Europe and the reaction from central banks will continue to dominate financial markets.”

AA

The UK’s new long-term credit rating after S&P’s downgrade on June 27

Markets steeled for Brexit fall-out

What next for UK’s economy as shock result signals ‘period of unprecedented uncertainty’ for investors?

The unexpected decision by the UK to leave the European Union has brought forward forecasts of recession in the UK and the need for clear actions by both governments and central banks.

As a political rather than an economic shock, the effect of the result on the economy is more indirect in the short term, delivered through the financial markets and the knock-on effects on business and consumer confidence, says Ian Stewart, Deloitte’s chief economist in the UK.

He explains: “[June 24] saw a flight from riskier assets, such as sterling and equities, to safer assets such as gold, government bonds, the yen and the dollar. If sustained, declining financial market risk appetite tends to feed through to weaker risk appetite in the corporate sector. Companies react by battening down hatches, paring investment and sharpening their focus on cost control.

The impact on global growth and inflation on the cyclical horizon is likely to be relatively small – and almost certainly not large enough to push the global economy into recession

“Foreign investors may also take fright and hold back on investing in the UK. Since the UK needs overseas capital to cover its current account deficit, the result of such a buyers’ strike would be a further weakening of the pound.” He points out that to generate a full-blown recession “consumers, who account for two-thirds of GDP, would need to stop consuming, as they did in 2009-10”.

But he adds: “The worry is that a toxic combination of uncertainty and a squeeze on spending power from high inflation and weaker earnings does just that.”

Dominic Rossi, global chief investment officer for equities at Fidelity International, noted on June 24 that the decision “will fundamentally change the way we administer our laws, our regulation and trade agreements. It leaves business leaders and investors in a period of unprecedented uncertainty for the UK. I think we have to realise there will be a negative economic effect in the immediate future.”

While Mr Rossi points out the UK economy has performed well in the past couple of years, he adds: “I think it’s unavoidable we will experience a recession. It will be mild compared with 2008-09, with rising levels of unemployment and falling demand and some relief from exports from a weaker currency. I see us coming out of this recession in 2017.

“I think this is a shock and shocks tend to hit economies relatively quickly, so I think we’ll probably start seeing signs of deceleration over the summer.”

A key element in stabilising the economy will be actions taken by the government and the BoE, with Mr Stewart noting the most useful response “would be for the government to signal the direction of travel for the UK in its negotiations with the EU. In markets and business as in life, intent matters”.

In the days following the referendum result, chancellor George Osborne ruled out the immediate introduction of a so-called “austerity Budget” that had been mooted in the run-up to the vote.

Tom Selby, senior analyst at AJ Bell, says: “While exceptional circumstances may require radical solutions, instant austerity through a knee-jerk ‘punishment Budget’ could have further destabilised an already febrile economy. However, this is likely a stay of execution rather than a full-on reprieve. If the economic warnings of the Treasury, the BoE, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and others are proved correct, the next prime minister and his or her chancellor will eventually need to wield the axe or raise taxes to balance the books.”

On the central bank side, Mr Stewart notes: “The BoE could undertake more quantitative easing, stepping up the volume and the range of assets purchased to boost liquidity and asset prices and drive down long-term interest rates. Inflation may head higher as a weaker pound pushes up import prices, but as a one-off phenomenon in an economy facing great uncertainties, such a temporary inflation would not justify interest rate rises.”

But until there is more confidence in the UK’s position, business investment and employment are likely to slow, which in turn will weigh on UK growth, warns Nikko Asset Management senior portfolio manager Simon Down.

“The BoE could react to this by reducing interest rates from 0.5 per cent to zero per cent, but it is likely to need some evidence that the economy is actually being negatively impacted before acting,” he says.

Meanwhile, one widely expected effect of Brexit is to make the US more likely to keep interest rates on hold. Jim Leaviss, head of retail fixed income at M&G Investments, suggests: “With the global growth outlook also now likely weaker, we expect the US Federal Reserve to be on hold. No rate hikes for the foreseeable future.”

Azad Zangana, senior European economist at Schroders, adds that having already put off a rate hike in June, the Fed “will almost certainly keep interest rates on hold for the rest of the year”.

Outside of monetary policy and interest rates, additional concerns include the potential for Scotland to hold a second independence referendum, with Scottish National Party leader and first minister for Scotland Nicola Sturgeon announcing a second vote is “on the table”, as well as plans to enter into discussions with the EU on “protecting Scotland’s place” in the organisation.

But while there are some concerns the UK’s vote could lead to similar calls for referendums in other European countries and a knock-on effect on European growth, the likelihood of a global recession appears slim.

Joachim Fels, global economic advisor at Pimco, says: “The impact on global growth and inflation on the cyclical horizon is likely to be relatively small – and almost certainly not large enough to push the global economy into recession. Even if the UK fell into a recession, the direct knock-on effect on global GDP through lower UK import demand would be minimal as the UK accounts for only 3.6 per cent of global imports of merchandise goods and 4.1 per cent of global imports of commercial services.”

Valentijn van Nieuwenhuijzen, head of multi-asset at NN Investment Partners, adds: “What we do know is that this is a political crisis that will not automatically trigger a worldwide recession or a liquidity crisis in the financial system. There is huge uncertainty politically and economically, especially for the UK. Recession there seems likely, but policy action will be key in determining how deep it will be.”

Eric Chaney and Laurence Boone, from the research and investment strategy team at Axa Investment Managers, add: “We expect a slowdown in the UK, starting to materialise in the third or fourth quarters – a recession being a possibility. Neither the US or Asia are likely to be significantly hit by the UK vote. Markets will unavoidably ask the question: ‘is this exogenous shock going to trigger a global recession?’ Our answer is probably not, but it is fair to say that uncertainties have increased.”

Nyree Stewart is features editor at Investment Adviser

ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

James Dowey, chief economist and chief investment officer at Neptune Investment Management, says:

“Investors should retain confidence in the mitigating effect of the policy response of central banks, even in the context of their somewhat frustrated attempts to generate accelerating growth and inflation in parts of the developed world during recent years.

“Central banks are much better at calming financial distress than they were even a decade ago. They have had a lot of practice in the interim, enabling them to develop effective tools to ‘learn by doing’ and build the confidence to act quickly. This was evident in BoE governor Mark Carney’s statement, in which he set out the contingency planning that the bank has prepared in the past few months and articulated its willingness to do whatever is necessary to stabilise the financial system.”

UK multinationals stand their ground

While the FTSE 100 has bounced, the FTSE 250 – along with some more high-profile names – has been harder hit.

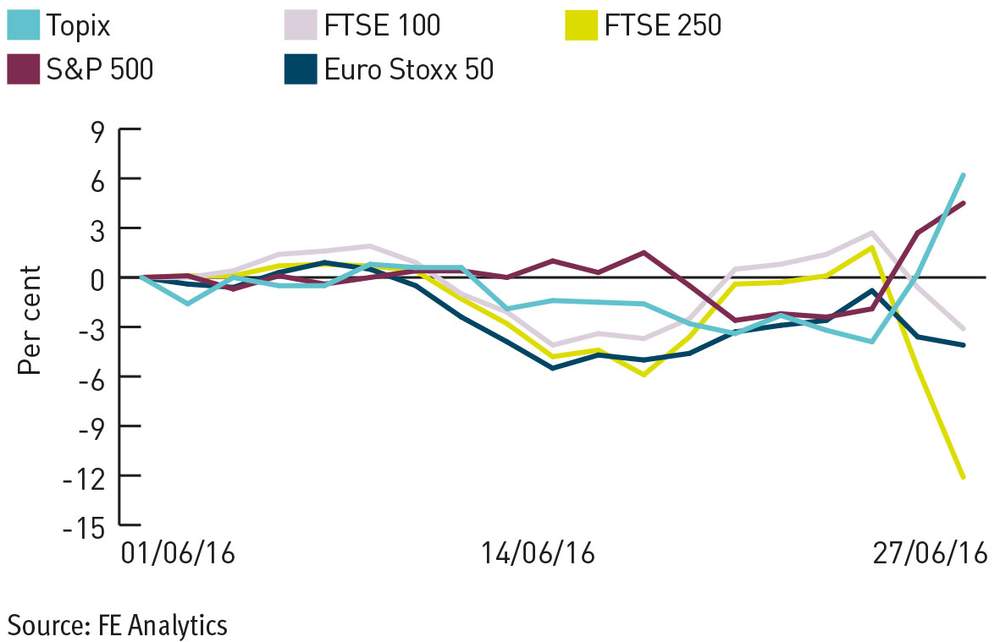

As the referendum result started to sink in, UK stockmarkets recorded sharp downward movements in the days following the vote.

After a swift sell-off, the FTSE 100 index rallied on June 24 to a loss of just 3.2 per cent, although this was followed by a further 2.6 per cent drop on June 27 before stocks started to move higher in spite of an S&P credit rating downgrade.

But, while large caps appear to have found more solid footing, the FTSE 250 has been harder hit, with falls on June 24 and June 27 of 7.2 per cent and 7 per cent, respectively.

UK multinationals with a strong global footprint and lucrative dividend income offer defensive alternatives to the Brexit event

Viktor Nossek, head of research at WisdomTree, notes UK mid- and small-caps whose business models are more focused in the UK or whose trade profile is more concentrated in Europe are more prone to the downside risks, adding that hedging UK mid- and small-caps “may be warranted, not least given that more than 50 per cent of UK trade is with the EU”.

In contrast he says: “UK multinationals with a strong global footprint and lucrative dividend income offer defensive alternatives to the Brexit event that, on net, may benefit from improved exports if the pound weakens.”

Laith Khalaf, senior analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown, points out: “While overall the FTSE 100 index has held up relatively well in the aftermath of the EU referendum, there have been some high-profile casualties, chief among them banks, house builders and airlines.

“Even in the banking sector there has been a substantial divergence in fortunes, with Lloyds seeing about a third of its value shaved off in two days, while HSBC came through relatively unscathed, suffering a price fall of around 5 per cent.”

Outside of the UK, European stocks also suffered with the Euro Stoxx 50 index slipping 3.3 per cent – in sterling terms – between the vote and the end of June 27, according to data from FE Analytics.

Rory Bateman, head of European equities at Schroders, says: “There are significant uncertainties how European authorities will react to this vote. It is likely spreads for European periphery markets will widen, which has implications for financials.”

Claudia Von Türk, global banking analyst at Lombard Odier, adds: “Though we expect weakness in the UK [banking sector], we believe the names in the periphery could be even weaker given contagion fears, notably in Spain but also in Italy.”

Italy faces a constitutional reform referendum in October, which is seen as a make or break for the current government.

She continues: “French banks, Nordics, Benelux and Swiss banks are less directly affected. However, there could be side-effects. If certain currencies, such as the Swiss franc and Danish crown, are perceived as safe havens, this might lead to even more negative rates – not a good thing for the banks.”

Meanwhile, some are highlighting the potential strength in US equities following the vote. The fall in the pound helped the S&P 500 post a 6.6 per cent return in the three days to June 27, and John Bilton, global head of multi-asset solutions at JPMorgan Asset Management, suggests US equities “could benefit from a flight to quality”.

Dominic Rossi, global CIO of equities at Fidelity International, continues: “The rise in European risk premia following the UK’s decision to leave the EU further strengthens our conviction that US equities will continue to outperform. The US economy is showing signs of a rebound in consumption and we feel that the weak earnings environment of the last two years is fading.”

In addition, Richard Turnill, BlackRock’s global chief investment strategist, notes the result has spurred a flight to safety among investors, potentially creating opportunities.

“With most asset valuations looking fair to expensive, however, it’s important to focus on relative valuations. The big takeaway for those seeking to buy into market weakness: be wary of notionally cheap assets that face challenges, for example domestically focused European assets like UK real estate and European banks, and instead focus on assets with relatively attractive valuations and positive fundamental drivers, such as quality stocks [and] dividend-growth stocks. Indiscriminate selling of risk assets could translate into buying opportunities in these assets, including in UK-listed stocks that benefit from pound depreciation.”

Nyree Stewart is features editor at Investment Adviser

KEY NUMBER

3.2%:The fall in the FTSE 100 index on June 24 following the vote

Still a safe haven?

UK bonds suffer in run-up to referendum, but ongoing demand for income should support spread markets.

Bond markets were taken aback by the outcome of the referendum on EU membership.

It may be the case the impact will be felt more acutely in equity markets, but fixed income investors will be wondering what they can expect to happen to credit markets and how they should be positioned.

Chris Iggo, chief investment officer, fixed income at Axa Investment Managers, observes: “Bond yields are lower because of the flight to safety. In the credit markets, spreads are wider because of the political and economic uncertainty that flows from the vote.”

The ECB’s corporate bond-buying programme should provide some strong technical support for European investment-grade issuers

He is optimistic there will be buying opportunities, though. “Central banks will provide liquidity, rate hikes are off the cards and bonds have better capital preservation characteristics than equities that face an uncertain earnings outlook,” he explains.

In the run-up to the referendum, figures from Thomson Reuters Lipper showed the IA Sterling Strategic Bond sector was one of the worst hit by investors pulling assets from UK funds, recording net outflows of £12bn over the year to the end of May. However, the IA Global Bonds sector was one of four IA sectors to see inflows of more than £1bn across the same period.

Jim Cielinski, global head of fixed income at Columbia Threadneedle, also highlighted that in the aftermath of the result, core government bond yields plunged to record lows, but suggests further declines should be limited.

“The price of so-called safe havens is now extreme,” he adds.

But he concedes: “Corporate issuers have become well-accustomed to operating in a low-growth, weak-revenue environment; for such companies, it will be the extent of economic weakness that matters most. Our central case is for slow growth, no credit improvement but no sharp rise in defaults.”

Mr Cielinski states: “Demand for income remains and this will support spread markets, as will a policy response that provides a ‘back stop’ and cushions losses in corporate bonds – such as corporate bond purchases, for example. We remain modestly constructive on corporate credit.”

Among the immediate responses from fixed income managers, there is speculation that the European Central Bank’s (ECB) quantitative easing programme will give the continent’s bonds an edge.

“The ECB’s corporate bond-buying programme should provide some strong technical support for European investment-grade issuers. Spreads will widen, but less so than if the programme did not exist, and the European investment-grade market should outperform the UK market – and possibly even the US market,” forecasts David Stanley, fixed income portfolio manager at T Rowe Price.

As to how UK investors will react, Newton Investment Management’s Howard Cunningham, a fixed income portfolio manager, says: “It is worth bearing in mind that, to the extent investors initially view the leave vote negatively and want to dump sterling assets, we doubt gilts will be top of their sell lists. Sterling corporate bonds face conflicting forces and greater uncertainty may ultimately lead to risk premia, such as higher credit spreads, particularly for UK-domiciled issuers.”

Ratings agency S&P responded by downgrading the UK’s credit rating to AA from AAA on June 27, citing the risk to economic prospects, fiscal and external performance.

Mr Cunningham disagrees with Mr Stanley on European debt, however, saying: “With yields on euro-denominated bonds already low, sterling corporate bond yields might look more attractive. Particularly if, as we expect, ECB intervention has unintended negative effects on liquidity in the euro corporate bond market.”

Mr Iggo says despite the surprise win by the Leave side, his views on fixed income do not change. “Investors still need yield, it will take time for the economic implications of Brexit to become clear, and there is a lot of cash to be invested,” he notes.

“Markets will settle but the referendum has probably put in place a series of events that will bring political and economic risk. Investors need to focus on basic principles when looking to generate returns. Bonds provide safety in uncertain environments and if there is going to be a need for additional monetary stimulus then fixed income benefits.”

Ellie Duncan is deputy features editor at Investment Adviser

EXPERT VIEW

What next for credit markets?

Pioneer Investments’ head of European fixed income, Tanguy Le Saout, says:

“We expect Brexit will cause a rally in German Bunds, accompanied by an under-performance of other markets, but especially peripheral markets such as Italy and Spain.

“A sharp ‘risk-off’ environment, accompanied by widening spreads in peripheral and credit markets could cause central banks to intervene. The central banks’ immediate focus will be on stabilising the markets, and they are ready to provide them with liquidity. We believe that monetary policy adjustments will be made, initially through measures of credit easing and broadening of the asset buy-back programme, but ultimately rate cuts may be implemented.”

KEY FIGURE

-0.1%: The yield on German 10-year bonds fell to -0.1 per cent on June 24, the day after the referendum.

A long and winding road

The ‘Leave’ vote is just the beginning of the UK’s arduous journey towards Brexit, and creates as many questions as it answers.

Britain’s historic decision to leave the EU has left many wondering what happens next. This question was asked of the ‘Leave’ campaign in the run-up to the referendum in the event they won a majority but, in the aftermath of the vote, the order of events appears just as uncertain.

This is in part because there is no precedent – no member state has ever left the EU.

The only certainties are that the UK does remain a member of the EU for now and will do for two years after Article 50 is triggered. Prime minister David Cameron also confirmed the day after the referendum he will stand down and will not start the Article 50 process – the task will be left to his successor.

The loss of passporting rights means firms will no longer have the right to carry on regulated activities in the EU

In its post-referendum investment update Rathbones says the vote to leave the EU should now trigger a formal exit process, but admits that, given the constitutional challenges and relatively close result, “this will not be straightforward”.

“The government [has chosen] to delay formal notification until the Conservative Party leadership situation is resolved and until its policy ducks are in a row. There is even a chance that the UK could remain in the EU – the referendum is not legally binding and parliament must vote to repeal the 1972 European Communities Act.

"Also, despite their rhetoric in the run-up to the vote, European leaders may well explore new ways to keep the UK in the EU,” the wealth manager suggests.

Chris Urwin, head of global research at Aviva Investors, explains: “Negotiations for exit do not start immediately. For that to happen, the UK needs to inform the European Council of its intention to invoke Article 50.

“However, the government may choose to start negotiations before triggering Article 50: once invoked, negotiations are limited to two years unless there is unanimous agreement of the European Council to extend them.

“So there is going to be a prolonged period of time during which the terms of our withdrawal from the bloc are unknown. It could take even longer for clarity on the UK’s terms of trade with partners around the world.”

One of the questions frequently asked during the run-up to the referendum was whether there are any models the UK could follow outside the EU.

As Amundi’s Philippe Ithurbide, global head of research, strategy and analysis, and Didier Borowski, head of macroeconomics, note: “The UK has several options: join the European Economic Area (EEA); draw on the existing model for certain countries (Switzerland, Norway or Turkey); or conform to the rules of the World Trade Organisation – the most costly solution for the UK as it is the furthest from the current situation. None of these solutions will please both parties at this stage.

“We are, therefore, heading towards ‘made-to-measure’ agreements with the EU, possibly supplemented by bilateral agreements. The timescales for negotiating these kinds of agreements are very long – on average, between four and 10 years to complete. At the end of the day, it is likely that the UK will remain part of the EU for more than two years.”

One industry in particular looking for answers in light of the vote for Brexit is financial services, which relies on EU passporting rights.

“The loss of passporting rights means firms will no longer have the right to carry on regulated activities in the EU,” outlines Paul Edmondson, head of financial services at law firm CMS.

“They will have two options: get themselves separately authorised in each EU country where they carry on regulated activities – not an appealing option; or set up a new group company in the EU. Once that new company is authorised by the regulator in the country where it is incorporated, it will have full passporting rights into all 30 remaining EEA states, but not into the UK.

“Large groups may end up with one company for EU business and one company for the UK and the rest of the world. The senior managers of the new company will need to be based in the country in which it is authorised.”

The passporting system has helped the UK become a global financial centre, with non-EU member Switzerland, for example, relying on London’s access to this process for its own financial services industry.

“Negotiations over financial services promise to be long and difficult as they are strategic for both the UK and the EU,” say Mr Ithurbide and Mr Borowski.

“The UK is the EU’s leading financial centre – it accounts for almost 25 per cent of the EU’s financial services and 40 per cent of its financial service exports. Financial services represent 8 per cent of UK GDP. Although no financial market is likely to replace London, the loss of a ‘European passport’ for UK banks is likely to lead to the relocation of certain business segments – to Ireland or certain EU markets.”

The ‘Leave’ vote also calls into question the future of the UK itself as Scotland, which overwhelmingly voted to remain part of the EU, has already begun pushing for a second referendum. If it votes to stay in the EU then the UK as we know it will break up.

There is also a risk other European countries will call a vote on their membership of the union, as anti-EU sentiment spreads across France and Italy in particular.

This adds another layer of uncertainty for both the EU and UK specifically.

“Uncertainty around the future shape of any deal would likely have to run concurrently with the strong possibility of a break-up of the EU and the UK,” point out Jan Straatman, global chief investment officer, and Salman Ahmed, chief investment strategist, at Lombard Odier Investment Managers.

“Contagion to Europe is possible as conjecture increases about the domino effect and as markets question which other countries may also opt to leave the EU.”

In other words, the outcome of the referendum in the UK raises a whole host of new questions.

But Larry Hatheway, group chief economist at Gam, observes: “For Europe, Brexit is the single-greatest challenge to European integration of the post-war period. Support for Europe cannot be taken for granted in an environment of rising dissatisfaction with its institutions. The EU must find a compelling message, but will it?”

Ellie Duncan is deputy features editor at Investment Adviser

EXIT MODELS

Trinity, an independent specialist hedge fund company, sets out the three principle exit models:

The EEA model

Remaining as an EEA country, rules such as the AIFMD and Mifid II would continue to apply but UK policymakers would have less say in their formulation.

The Swiss model

This means joining the European Free Trade Association and negotiating access to the single market.

The World Trade model

A complete withdrawal would designate the UK as a third country. This would have a more noticeable impact as Britain may have to rely on its World Trade Organisation membership to negotiate trade deals.

WHAT NEXT FOR THE EU?

Ian Stewart, Deloitte’s chief economist in the UK, says:

“More extreme political parties, such as the Freedom Party in Austria and the Front National in France, are gaining ground. The immediate concern is the risk of a domino effect as Eurosceptic parties elsewhere demand their own referenda. Recent research conducted by Deloitte and the German employers’ organisation BDI found that 66 per cent of German businesses believe a British exit would lead to further such votes.

“A complicating factor for UK negotiations with the EU is a series of national elections: in the Netherlands (March 2017), France (April to May 2017) and Germany (August to October 2017). It is possible that Europe’s de facto leaders, Angela Merkel and François Hollande, will leave office in 2017.”

KEY NUMBERS

40% Of the EU’s financial services exports are from the UK

8% Financial services represents 8 per cent of UK GDP

Source: Amundi